4th Annual Chili Cook-Off

November 2nd, 202411 am-2 pmSt. Rita School for the Deaf1720 Glendale Milford RoadCincinnati, OH 45215 Come out and taste chili samples from all contestants to vote! $10 Per Person. Think your chili is better than others, challenge yourself, and join the contest to enter your chili! $20 to enter and register here: https://forms.gle/6AujuZBfbcPbeY7s5 New this year!…

Winter Wonderland

Hearing Speech + Deaf Center is hosting a free Winter Wonderland event for children on Saturday, December 9, 2023, from 10a.m. to 1p.m. The event is at the Center’s Corryville location, 2825 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati. Pre-registration is required for this event. Children attending Winter Wonderland will get a “magical passport” to explore holiday traditions around…

Save the Date: 7th Annual Laura and Richard Kretschmer Service Award Gala

Please join us at our 7th Annual Laura and Richard Kretschmer Service Award Gala. The event raises critical funds to extend healthcare access for services and treatments of communication disorders and deafness to patients with low incomes and wealth. Please consider a sponsorship or gift to recognize this year’s honorees. Sponsor Details Thursday, May 11,…

2022 Annual Gala Gallery

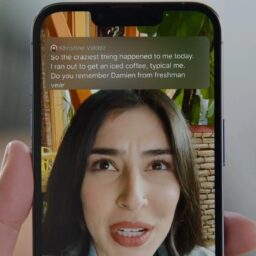

Captions are cool!

Wall Street Journal recently reported on a May survey of 1200 Americans who use captioning for videos. The results are surprising to some. WSJ: “In a May survey of about 1,200 Americans, 70% of adult Gen Z respondents (ages 18 to 25) and 53% of millennial respondents (up to age 41) said they watch content…

Susan and Sam

A personal tragedy led Susan to be all-in for kids like Sam. A July 28 Gala celebrates Susan and cheers for #ShiningStar Sam’s progress. The Gala delivers critical funding to our 501c3 programs for deafness, hearing loss, and speech disorders. Tickets and sponsorships to support Susan and Sam and our mission for #CommunicationEquity, #Inclusion, and…

Hearing Speech + Deaf Center receives funding for Connections for Life from SC Ministry Foundation

Program treats children affected by complex trauma CINCINNATI, July 1, 2022 – Hearing Speech + Deaf Center’s Connections for Life (CFL) program has received an investment from the SC Ministry Foundation. The CFL program treats children (toddlers to teens) who experience chronic and complex trauma ‒ exposure to adverse experiences such as violence, abuse, neglect,…

Board member, Jack Wyant, is recognized with Life Achievement Award

Congratulations to our board member, Jack Wyant. Jack will receive a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cincinnati Chapter of the Association for Corporate Growth on Wednesday, June 22. Previous Lifetime Honorees have included luminaries such as James Anderson, John Barrett, Bob Castellini, Richard Farmer, Candace Kendall, AG Lafley, Glen Mayfield, John Pepper, Ted Robinson, George…

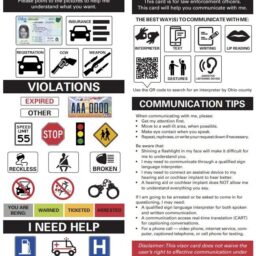

A new communication card will help deaf and hard-of-hearing Ohioans communicate with law enforcement

Governor Mike DeWine announced the Ohio Department of Public Safety’s Traffic Safety Office (OTSO), Opportunities for Ohioans with Disabilities (OOD), and statewide law enforcement partners have developed a new communication card to help individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing exchange information with law enforcement. The new communication card can help individuals who are…

Universal live captioning coming from Apple

TechCrunch is reporting about new accessibility features coming from Apple later this year. Live captioning is among the most widely applicable new feature. With it, captions of spoken content from videos, podcasts, FaceTime, and other calls will appear in a speaker-specific scrolling transcript above the video windows. See the TechCrunch story here for more details….